surrealism's "open letter"

On Deafman Glance, friendship, and the legacy of the French avant-garde

Greetings readers! For the third installment of minor archives, I will be examining a letter that is well known in the history of avant-garde performance, but that perhaps deserves a reconsideration as a literary event on its own terms.

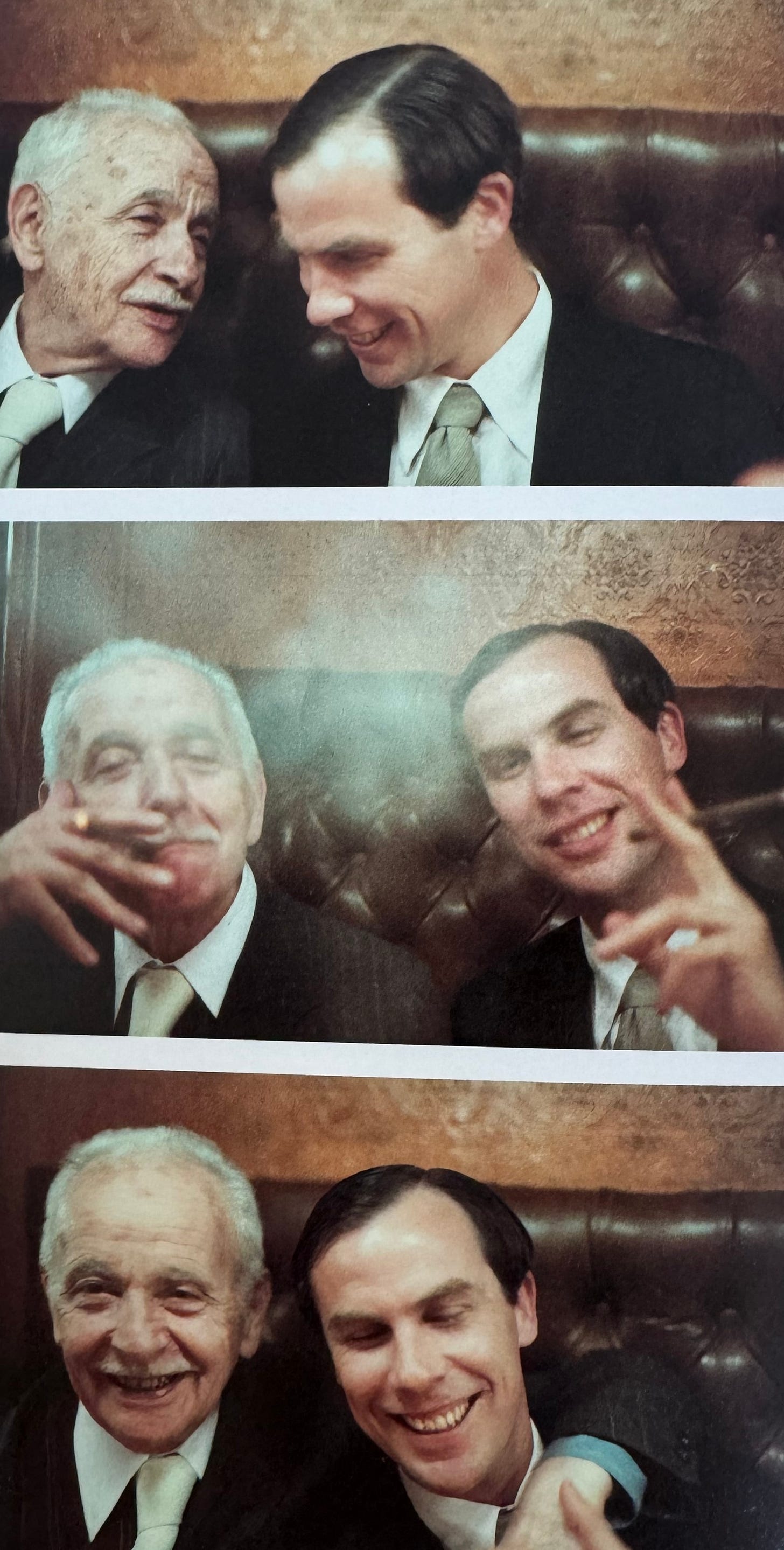

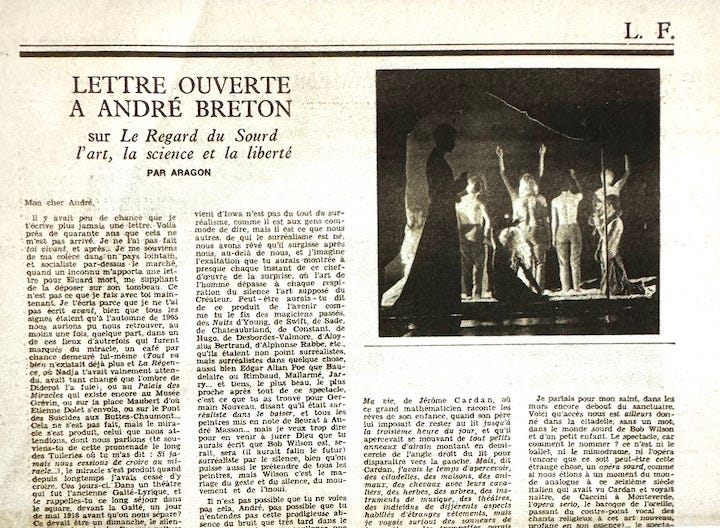

On June 2, 1971, the French poet and political activist Louis Aragon published a short article titled “Lettre Ouverte à André Breton sur Le Regard du Sourd: l’art, la science, et la liberté” in Les Lettres Françaises. It appeared after the American theater director Robert Wilson’s play Deafman Glance had premiered in France at the Festival de Nancy in April and just before it opened on June 11 at the Théâtre de la Musique in Paris. Breton and Aragon had founded the surrealist movement in France in the late 1910s and Breton had died in 1966. Aragon’s “letter”, addressed to his dead colleague, declares that Deafman Glance (or Le regard du sourd, as it was known in France) was “what we dreamed [surrealism] might become after us, beyond us.”[1] This public acknowledgement from Aragon, which effectively anointed Wilson as the creative heir to the movement, was instrumental in establishing the director’s career in Europe.

(above: Louis Aragon and Robert Wilson in Paris, 1971. photographer unknown)

Although this document has been considered in the context of Wilson’s trajectory toward global recognition and the history of American avant-garde performance, there is much to be gained through a reading of the letter as an important literary event in the context of twentieth-century French thought. Why did Aragon choose the letter as his format? Why write to Breton, his estranged friend who had been deceased for seven years? What was the letter’s implication for the French Left?

Surrealism originated in the late 1910s as a literary movement that was influenced by ideas of the unconscious developed by Freud as well as the radical politics of Marx. Breton and Aragon, along with the writer Philippe Soupault, founded the surrealist journal Littérature in 1919 and began experimenting with automatic writing. Breton consecrated the movement through the publication of The Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924 and the movement grew to become associated with the visual arts. In 1927, Aragon became an official member of the French Communist Party (PCF). In 1932, he broke with Breton and the surrealists after being accused of inciting violence in his poetry and engaging in fierce internal debate about the relationship between art and politics, an episode which became known as the “Affaire Aragon”.[2] He was drafted into the army in 1939 and received medals for bravery at Dunkirk. He became an active member of the National Front resistance movement after he was demobilized. Following the war, in 1953, Aragon became director of Les Lettres françaises, the literary supplement of the PCF’s party newspaper, L’Humanité, and ran the publication until it closed after losing communist support in 1972, just one year after the appearance of his letter to Breton.

At the time of Aragon’s publication of the “open letter”, surrealism had been canonized in the French cultural memory as the last great “French” artistic movement, before the war had transplanted the European avant-garde to the United States. By the 1960s, the impact of the movement had been traced to Latin America and throughout the United States. What had begun as a radical Leftist movement was now claimed and beloved by the French establishment. That Louis Aragon, the politically committed surviving figurehead of this movement, actively proclaimed the passing of its legacy to Robert Wilson, a 27-year-old Texan, is evidence of his interest in intergenerational exchange, global impact, and the legacy of surrealism’s artistic and political values.

(above: Sheryl Sutton on the cover of L’Officiel des Spectacles, June 16-22, 1971).

Although the subject of Aragon’s letter is Wilson’s new work, its purpose, I would contend, is to reconcile the history of surrealism’s French identity with its contemporary legacy. Aragon greets his former friend by acknowledging their rupture:

“My dear André,

It isn’t very likely I would ever write you another letter. It’s already been forty years. I didn’t do it with you living, and afterward…I remember my anger in a far away country, a socialist one at that (but that’s neither here nor there) when a stranger brought me a letter for the dead Eluard, begging me to place it on his grave. That’s not what I am doing now for you. I write because I didn’t write before, even though all the signs showed that in the autumn of 1965 we could have found each other in one of those places from the past that was marked by miracles…It didn’t happen, but the miracle was produced, the one we had been waiting for, about which we talked (remember that walk the length of the Tuileries, where you said, ‘If we ever stop believing in miracles…’) the miracle came about long after I stopped believing in them.”[3]

The letter plays with literary tenses, referencing both the past and the future. Aragon moves backwards and forwards in time by reconciling a forty-year-old dispute with a once-cherished colleague while simultaneously declaring the continuation of their friendship’s creative legacy. Its epistolary form creates a further sense of intimacy. The use of first person here, perhaps in contrast to the public “pamphlets” produced around the Affaire Aragon debates in the 1930s, shifts the narrative emphasis from public action to private experience, which is of course then made public through the use of the open publication format.

Epistolary narrative, more generally, explores the realm of the private through the immediacy of its expression and ability to convey compelling descriptions of subjective emotion. The format of Aragon’s letter thus aligns with the experience of seeing Wilson’s play, which leans into the singularity of subjective perception. Deafman Glance explores the world of a deaf, non-speaking Black boy named Raymond Andrews through the use of slow, dreamlike images. The luminous Sheryl Sutton, a student at the University of Iowa whom Wilson met while workshopping the play before its premiere in December 1970, is featured as the boy’s mother. The work aims to explore the heightened sensory perceptions of Andrews’s subjective position, reparatively considering Andrews’s lived experience in a differently abled body. However, Andrews’s experience at the center of the play is ultimately framed by whiteness–by Wilson’s staging, the gaze of the (largely white) European audiences, and the contemporary critics and scholars that wrote about the work. Yet, the work’s investigation of how we speak through movement and images in the absence of language allows us to imagine the world differently, by exploring the gaps between word and image, speech and movement, dialogue and sound.

Aragon writes, “For more than four hours, we went to inhabit this universe where, in the absence of words, of sounds, sixty people had no words except to move. I want to tell you right away, Andre, because even if those who invented this spectacle don’t know it, they are playing it for you, for you would have loved it as I did…”[4]

By turning toward the past to look forward, Aragon incorporates the American avant-garde into the history of French humanism–or rather, offers French affinity to the trajectory of American art.

(above: Louis Aragon’s letter to André Breton in Les Lettres françaises, June 2, 1971)

[1] The English translation I reference here is by Linda Moses with the assistance of Jean-Paul Lavergne and George Ashley. It appeared as Louis Aragon, “An open letter to André Breton from Louis Aragon: On Robert Wilson’s Deafman Glance” in Performing Arts Journal (Vol. 1, No. 1 Spring 1976): 4.

[2] Donald Kuspit, “Dispensable Friends, Indispensable Ideologies: André Breton’s Surrealism” in Artforum (December 1983): 56-63.

[3] Aragon, 4-5.

[4] Aragon, 5.