Greetings readers! This week’s post is an ode to a memoir I read back in May while I was in Paris working in various archives and libraries. It speaks to the various entanglements that writers encounter in the course of researching living subjects. For me, reading this memoir was both instructive and comforting. It reminded me of the value of finding literary camaraderie in the process of writing, which can too often be an isolating endeavor.

Parisian Lives: Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir, and Me: A Memoir (Penguin Random House, 2019) chronicles the fifteen years that Deirdre Bair spent working in Paris while writing the biographies of Samuel Beckett and Simone de Beauvoir. In 1971, Bair was a newly minted PhD, mother of two young children, and a journalist. She had not yet written a book and, accordingly to this memoir, had never read a biography. To her surprise and delight, Beckett agreed to allow her to write his first biography. At the time, interpretations of his work painted him as a melancholic and despairing figure whose work was abstracted from everyday life. She was the only one who recognized the connection between his art and life–portrayals of actual people and places from his childhood in Ireland.

Bair describes her first meeting with Beckett in the opening sentences of the memoir:

“’So you are the one who is going to reveal me for the charlatan that I am.’ It was the first thing Samuel Beckett ever said to me on that bitter cold day, November 17, 1971, as we sat in the minuscule lobby of the Hôtel du Danube on the rue Jacob. I had gone to Paris at his express invitation, to meet him and talk about writing his biography. We were originally scheduled to meet on November 7, and for ten days I had no idea where he was, because he never showed up and never canceled.”[1]

Later in the meeting, he tells her, “I will neither help nor hinder you. My friends and family will assist you and my enemies will find you soon enough.”

Bair’s book recounts the whirlwind process of writing her first book while dealing with the demands of raising a young family, an academic career, sexism from the male-dominated field of modernist literary studies, and the factionalized world of Beckett’s social milieu.

At the time, she was told by her academic advisor that writing a biography would be “career suicide.” Nevertheless, Samuel Beckett: A Biography won the National Book Award in 1981.

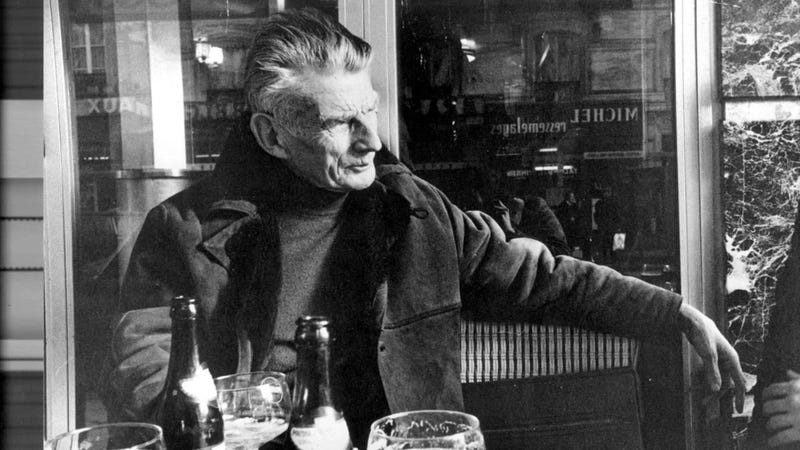

[Samuel Beckett in Berlin. Still from Samuel Beckett, film by Rosa von Praunheim, 1969.]

Her process of writing de Beauvoir’s memoir was much smoother, although challenging in its own regard. De Beauvoir died just as she was finishing her first draft. Her subject had integrated her into the French literary community and her experience with de Beauvoir’s circle was much warmer. During this process, her former advisor’s warning proved to be disturbingly prescient when she was denied tenure after teaching for many years in the English department at the University of Pennsylvania.

Overall, Parisian Lives is a delightfully gossipy read, and there is much to unpack, but what I found most resonant at my own stage of life and writing is how messy writing about real subjects can be, living or dead. There are a range of sources–“living archives” in the form of people who know something special about your subject–that you must cultivate and manage. I count myself among those who work well with artists, and despite all the skills I’ve learned, it can still be excruciatingly complicated.

To illustrate one example, Bair recounts the problem of dealing with sources whose memories have shifted:

“There is often a significant contingent of people whose memories of their interactions become…far, far removed from reality. Some people I talked with exaggerated their roles, often in a direction far from their actual closeness with Beckett. Those who helped sometimes wanted to distance themselves from the written life, while some who put serious obstacles in my path lost no time in claiming that I could not have written the book without their constant guidance.”[2]

I was relieved to read Bair’s accounts of exhausting interviews, coy subjects, pushy interlocutors, and complex friendships. This was not only because she understands how large projects require management of a network that is scaled up from the kind of training that academics normally receive, but because she is also forthcoming about what she describes as her “naïveté” and the process by which she learned in trial by fire scenarios. Bair is not the only biographer I’ve read who recounts being propositioned for outrageous favors (sometimes illegal) in exchange for access to information.

[Simone de Beauvoir (left) with Deidre Bair. Photograph: Lavon H. Bair/Deirdre Bair]

Research can be a wild ride. There is a balance between scholarship and journalism that brings a writer into contact with new communities. Working on a long-term project is always an adventure. Each process reflects its subject, expressing a unique tone, structure, style, and shape. Twists and turns at every corner. Unexpected pivots. Or, conversely, a gentle rhythm punctuated by elegant flourishes. Sometimes, on and off the page, it can be a ride worth chronicling.

[1] Deirdre Bair, Parisian Lives: Simone de Beauvoir, Samuel Beckett, and Me: A Memoir (New York: Penguin Random House, 2019), 1.

[2] Ibid., 56.