Greetings readers! In this week’s installment of minor archives, I am sharing some information and thoughts on a little known but crucial figure in the world of international avant-garde theater, Ninon Tallon Karlweis (1908-1977).

Madame Karlweis, as she was known in the performing arts community, worked as a booking agent for theater artists and musicians in the mid-twentieth century. She was responsible for introducing many European artists to American audiences and organizing the early tours of American postmodern artists in Europe. Maintaining an office in Paris and an apartment in New York, she worked between the two countries as a business diplomat, accountant, booker, and friend of many international artists.

Ninon Tallon was born in Épinal, France into a well-connected political family. She met and fell in love with the actor Oskar Karlweis, an Austrian Jew who had fled from Germany to France. In 1940, Karlweis left France for New York to escape the German Occupation and in 1946, he and Ninon married in New York. According to Bénédicte Pesle, Ninon’s family rejected the marriage based on Oskar’s religion; however, she was deeply in love with him and followed him to New York.[1]

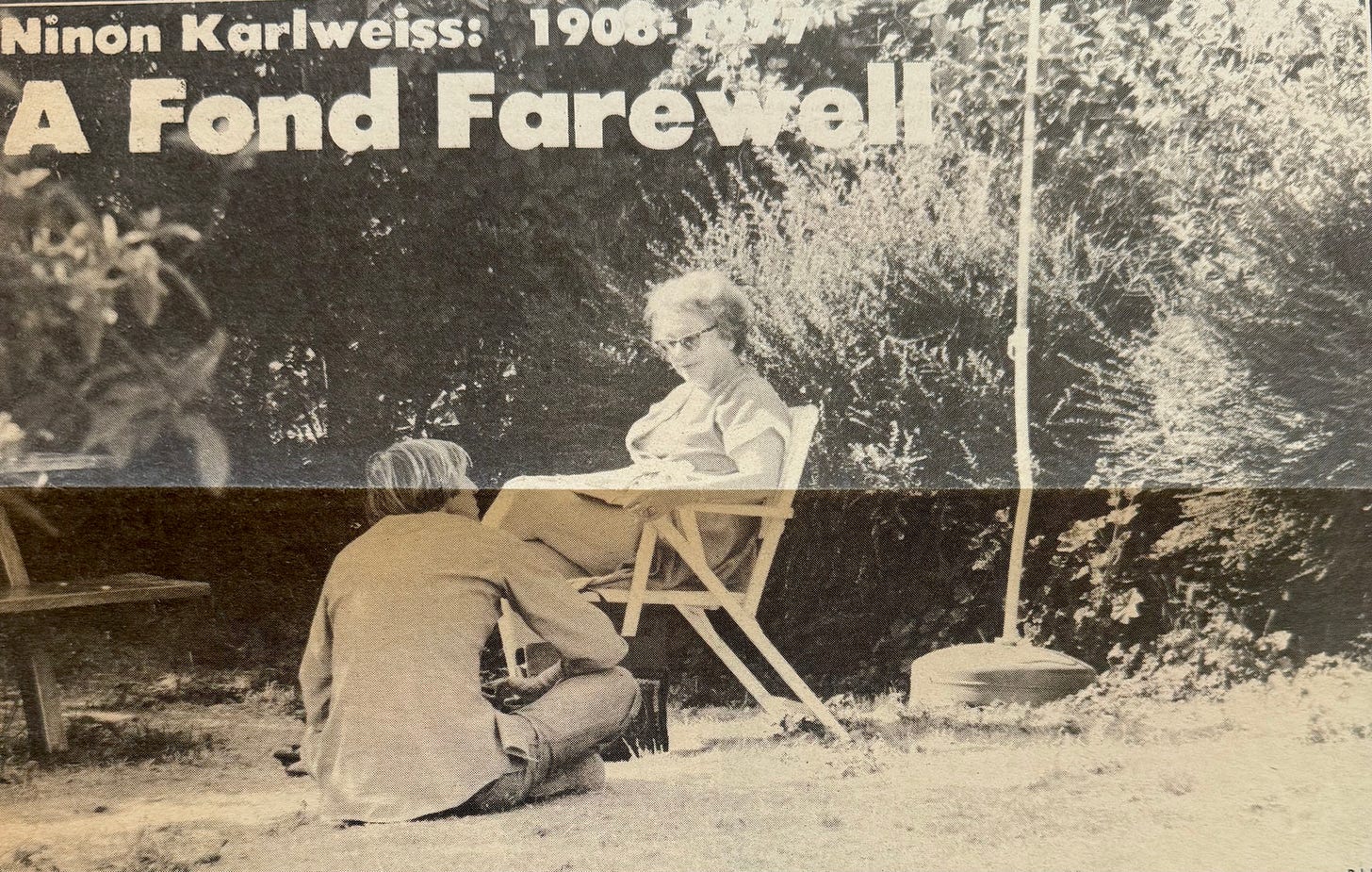

[Andrei Serban and Ninon Karlweis, La Rochelle, France, 1976. photo by Rob Baker.]

Operating as a sole proprietor under the enterprise “Office Artistique International” at 52 Avenue des Champs Elysées in Paris and 250 East 65th Street in New York, Ninon brought Eugène Ionesco’s play Rhinoceros, co-starring Zero Mostel, Eli Wallach, and Anne Jackson, to American audiences in 1961. She helped bring Bread and Puppet Theater to the Nancy World Theater Festival in 1968 and brought Jerzy Grotowski’s Polish Lab Theatre to the Brooklyn Academy of Music in the fall of 1969. One year later, a former Bread and Puppet actor named George Ashley (and another downtown legend, more on him soon) was working as an administrator for the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds, the downtown theater collective run by Robert Wilson. He told Ninon about Bob Wilson’s work, who relayed the information to Jack Lang, the founder and director of the Nancy World Theater Festival. After the presentation of Wilson’s work Deafman Glance in France established his career, she acted as the booking agent for his subsequent productions until her death in 1977. She arranged the contract for Ouverture in Paris and KA Mountain at the Shiraz Festival in Iran in 1972, booked the world tour for A Letter for Queen Victoria in 1974, and booked engagements for the tour of Einstein on the Beach following its 1976 premiere at the Festival d’Avignon.

Ninon worked closely with Bénédicte Pesle at Artservices. Wilson’s A Letter for Queen Victoria engagements were co-signed by the two agents, both stated as “representing” the Byrd Hoffman Water Mill Foundation. She also worked with many other artists, some of whom overlapped with Artservices: Richard Foreman, Meredith Monk, André Gregory, Joe Chaikin, Charles Ludlam, Andrei Serban, and Ellen Stewart. She was a generation older than these artists, producers, and agents, and when she died in 1977 at the age of 68, the theater world mourned her deeply.

By many accounts, she embodied a stately presence. Lew Bogdan describes her as, “an elegant and cultivated woman who shuttled between the Americas and Europe in pursuit of rare pearls.” She was well known for falling asleep during performances, and “in a kind of mysterious gift of lucidity” being able to recount exactly what had transpired onstage in detail afterwards.[2]

She was considered mysterious and legendary, even during her lifetime. In a heartfelt obituary for The Soho Weekly News, Rob Baker wrote, “A whole host of legends grew up around Ninon Karlweiss [sic] even as she lived: about her age, about her being a baroness or countess, about her having this or that advanced degree from the Sorbonne, about her being fabulously wealthy and footing the bill for the whole world of avant-garde theater. Most of these, I think, were not exactly true, but we are fascinated by the stuff that such dreams are made of, and I don’t think that such legends necessarily need to be laid to rest.”[3]

It is worth considering what the creation of such legends brings us. I confess that I am still learning about her, as there are few written accounts about the specificity of her involvement in the field of the performing arts. Documentation on the facts of her life are sometimes conflicting. Her name sometimes appears as “Karlweis” and sometimes it is spelled “Karlweiss.” As such, she is still somewhat of a mystery–even 47 years after her death.

In her New York Times obituary published on September 10, 1977, the Iranian delegate to the United Nations, Fereydun Hoveyda, is quoted as saying, “If ever there is a contest for Our Lady of the Festivals, as Madame Karlweis is fondly referred to, it will most likely be won by her.”[4] She served as a kind of patron saint of artists, a motherly figure who presided over the international productions of a range of younger theatre-makers.

In the tradition of the theater, she was also a self-made woman who seemed larger than life. Her “legendary” aspects, whether based in truth or not, functioned as narratives that amplified her impact. To be “legendary” implies that one’s reputation precedes one’s entrance, that it lingers after one’s departure and that it changes through time. The creation of myths–stories that are passed through generations–are especially important to artistic communities because belonging means adopting a chosen lineage that reflects the kind of person, or artist, you recognize as your spiritual kin.

Rob Baker continued, “The truth is that Ninon Karlweis was simply (simply?) [sic], an expert businesswoman who happened to love theater—new and exciting theater—and she made it her mission to bring out the things she loved to others around the world who shared that wonderful obsession.”

By sharing her love of theater with a range of international audiences, she brought together artistic community for a new generation.

[1] Bénédicte Pesle, video interview with Lucinda Childs, 2011.

[2] Lew Bogdan, Comme neige au soleil: Le festival Mondial du Théatre, Nancy 1963-1983 (Paris: Éditions L’Entretemps, 2018), 67. Translated by the author.

[3] Rob Baker, The Soho Weekly News, September 22, 1977, pages 17 and 43.

[4] “Ninon Tallmon Karlweis Dies at 68: An International Theatrical Agent” in the New York Times, published September 10, 1977.

I remember the day of this photo in La Rochelle... I was there!